Saul Villeda, an emerging PhD student, who had spent the past year conducting research that aimed to understand how blood affects the brain. They thought that some molecules contained in blood might be able to reach the brain and cause detrimental changes. The hypothesis was not as absurd as it might sound.

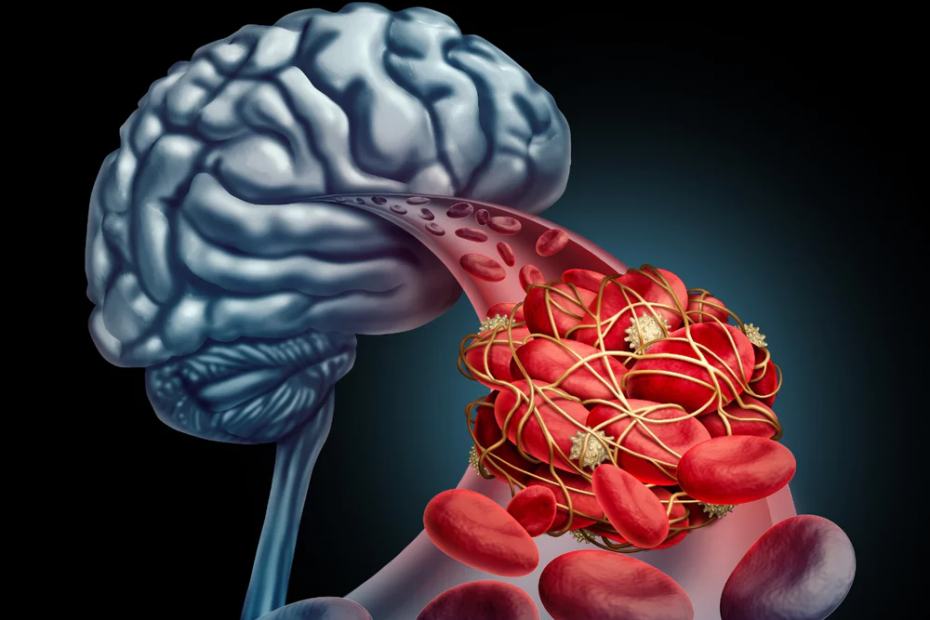

Villeda conducted pilot studies with mice: young mice received blood from old mice, and old mice received blood from young ones. Villeda wanted to see the effect on their brains. Something which could have never been done in a living human being. And what did Villeda find? Well, neurons in brains of young mice receiving old blood were unable to be regenerated, the neurons started to die, and ultimately young mice brains shrunk and became less functional. A region called the hippocampus, crucial for the process of brain cell generation, or neurogenesis, was one of the first to deteriorate, causing damage to mice’s memories and ability to process new information. Villeda asked: “Why is this happening?“ What is it that “old blood” contains that is different from “young blood”?” The answer was simple: inflammation.

Body inflammation is regulated by our immune system, the defensive response which protects us against threats, such as infections. Villeda found that some inflammatory proteins contained in the blood of old mice were responsible for the damage of brain cells of young mice. Most importantly, he found that young mice receiving old inflamed blood exhibited cognitive impairments, including memory and learning deficits, similar to those found in patients with neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s.

Why is this research important?, well, interestingly enough Villeda’s findings could be of relevance for other types of brain and mental health conditions. Indeed, patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, like depression, are known to share similar inflammatory features with Alzheimer’s patients. Strikingly, at least a sub-group of depressed patients had a high level of inflammatory proteins in blood, a reduced number of new generated cells in the brain, and show cognitive impairments similar to those described above for patients with neurodegenerative conditions. This seems to suggest that in patients with depression, similarly to those with Alzheimer’s, blood inflammation is somehow involved in the changes occurring in the brain, and might also contribute to the development of the clinical symptoms of depression.

In another study wanting to duplicate Villeda’s findings and using a research model made up of human brain cells (not mice!), we exposed cells to blood from patients with and without depression, and we counted the number of new brain cells generated. Something which, again, could have never been done in a living human being! From our investigations, recently published in the journal of Brain, Behaviour and Immunity, we were able to demonstrate that blood from depressed patients can reduce the number of new generating brain neurons and increase the number of dying cells, when compared with blood from non-depressed patients. We once again asked, “why this was happening?”, The answer, again, was simple: inflammation.

Overall, this seems to suggest that depression, similar to other neurodegenerative disorders, is not an “all in the brain” condition, and that the complex inflammatory environment characterising our blood can affect the life and health of our brain cells, ultimately predisposing the individuals to the development of the symptoms associated with those pathologies.

Although, evidence exists for other blood factors to regulate neurogenesis, ours and Villeda’s findings, unequivocally propose blood inflammation as among one of the major culprits. This, in turn, can have a crucial impact for patient’s therapeutic approaches.

If we manage to develop new drugs targeting those blood factors, we might be able to prevent brain cells degeneration and ultimately improve patients’ symptoms. Currently, molecules that block the action of specific inflammatory proteins have been tested in clinical trials for depression (see, for example, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02473289), or as antiviral strategy, which could be re-purposed for psychiatric indication.

One day, these new therapeutic interventions might become effective antidepressants, and will be prescribed to those patients having high levels of inflammation.

References

Website: https://medium.com/inspire-the-mind/your-blood-changes-your-brain-new-insights-on-how-blood-inflammation-affects-the-life-of-brain-c13c967d0e3e